Children In A World Of Violence

|

By Jane Sutton-Redner

In this story:

The daily news reminds us that there is always a war going on someplace in the world. One subsides, another breaks out. Often lost in the sheer magnitude of global violence is its devastating and increasing impact on children. An estimated 2 million children have died in the last decade, 250,000 forced to participate in fighting, and thousands more killed or maimed by land mines. Survival is just the beginning; children’s wartime experiences require long-term physical and psychological recovery. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Plight of Children in War

Battlefields were once the domain of warriors whose almost universal code of conduct was to protect civilians, especially women and children. "The civilian population...shall not be the object of attack. Acts or threats of violence the primary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population are prohibited," reads an addendum to the 1949 Geneva Convention regarding military protocol in war. Yet the exact opposite has become commonplace in recent and current conflicts.

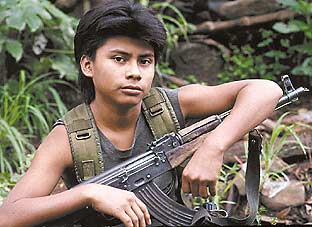

During the war in the former Yugoslavia which killed 15,000 children, youngsters were not just caught in the crossfire, but intended victims. In Sierra Leone’s bitter rebel conflict, the Red Cross estimates that more than 4,000 children died, accounting for almost 10 percent of all deaths. Child wartime deaths are not always from artillery. Many countries, poor even before the onset of war, see a breakdown in health, sanitation and water systems, leaving children more vulnerable to even basic disease. In Peru, Shining Path terrorists raided the countryside in Ayacucho province and rendered road travel precarious. Many children died of fevers, viruses and diarrhea because medicine and health workers could not reach them. Between 1981 and 1988, while a protracted civil war waged in Mozambique, 454,000 children died above the expected mortality, victims of the lack of medical care as well as violence. Hospitals are also more likely to be damaged or destroyed in modern warfare. In Grozny, the capital of the breakaway Russian republic Chechnya, only three of the city’s 13 medical facilities still functioned in 1996 after the Red Army’s heavy shelling. Children face a further threat from war - emotional and mental damage. Some 10 million of the world’s children suffer psychological trauma as a result of war experiences. UNICEF found that almost 80 percent of Rwandan children witnessed atrocities during the country's 1994 massacre of 1 million people. But even if youngsters do not witness violence or lose family members, they suffer the disruption of their normal lives as schools close, friends disperse, and their homes come under fire. In the short-term, children may stop speaking and become emotionally withdrawn. Some are permanently changed. "For children, the deepest scars of war and flight are the hidden ones," said Graca Machel, former Minister of Education in Mozambique and the author of the ground-breaking 1996 UNICEF report, "Impact of Armed Conflict on Children." Loss of childhood and education, and the horror of flight, rape and forced combat "[cut] deep into the psyche of children," Machel explained in an acceptance speech for a humanitarian award. The results can be loss of trust, aggressive behavior and tendency toward revenge, which, in time, may manifest in another cycle of violence. The jarring image of a child or young teen swaggering under the weight of an automatic weapon has recently become common in news reports from Africa’s troubled nations. Chillingly reminiscent of scenes of kids playing soldier, it represents a shocking, worldwide trend: More than 250,000 children under 18 are combatants in current conflicts, an unprecedented number. Necessity is not the driving cause for the increasing number of child soldiers; only a serious breakdown of values and human decency can account for cultures that place their young in harm’s way. While the international minimum age for children in armed conflict is 15, children younger than 10 have gone to war.

Some join fighting forces voluntarily. But others have no choice. They are forced or abducted into soldiering. The Lord's Resistance Army, a terrorist movement in Uganda has developed international notoriety for its use of child soldiers. Its leaders have been known to kidnap thousands of children, some as young as 8, from their homes and schools. They beat and abuse their captives into submission and turn them into merciless killers, fighting against the Ugandan government or in neighboring Sudan. Girls become soldiers’ wives; younger children run errands and carry loot. They not only witness countless atrocities, but also often participate in them. In gruesome initiations, new recruits are forced to kill another child- often a sister or brother - or be killed themselves. Much more is known about the issue of child soldiers in the wake of UNICEF's report, "Impact of Armed Conflict on Children." Humanitarian groups have also begun documenting former child soldiers' stories in the course of developing rehabilitation and counseling programs for these youth. These reports depict a nightmare that would defeat most adults. In some places such as Burma and Sierra Leone, drugs and alcohol blur the trauma of witnessing and participating in extreme torture and killing. In Liberia, rebel factions mixed myth and magic in the training of young soldiers, convincing them that they were invincible against bullets - then sending them into the thick of battle. The trauma doesn't end with their "tour of duty." Once the children escape or are rescued, they face alienation in their home communities and even their families, who understandably fear what the youths have become. Killing is their only skill; hand-to-mouth survival their only reality. Nongovernmental organizations have taken the lead in operating trauma centers to provide physical and psychological care for former child soldiers, who come out of the bush sick, injured, undernourished, and antisocial. Once children respond to medical help and counseling, they can be taught skills and help out around the center, which also raises the children’s self-esteem. Then caregivers track down the children’s families (many may have been displaced by fighting) and work to convince communities to welcome the children back. However, even after rejoining the community, the former soldiers' mental scars persist. In Kashmir,where children are forced to fight with rebels against India's government troops, doctors found a 10 percent increase in children's psychiatric disorders since 1989. "For our children, 'A' stands for army, 'B' for bullet and 'C' for curfew," Kashmir academic Muzamil Jaleel reported in Child Newsline. Children playing in a field or collecting firewood come upon small but insidious scraps of a recent or long-past war. With a click, then a blast, their lives are lost—or if they're lucky, just one or two limbs. Some 110 million land mines threaten children in more than 70 countries with this very scenario. Antipersonnel mines, or land mines, were created to eliminate mine clearers before they could remove the larger antitank explosives which detonate under heavy vehicles. There are hundreds of models manufactured by at least 24 countries. Some are strategically placed by hand, but most are dropped out of aircraft and randomly sown into the soil with no record of their placement. Many are virtually undetectable. Each one costs $3-$30 to make, lasts as long as 50 years, and costs up to $1,000 to remove before it maims or kills. Mines are cheap to use, yet they do the work of snipers without needing orders or compensation. And according to the International Committee on the Red Cross, they are chillingly effective: 82.5 percent of amputations performed in ICRC hospitals are for land mine victims. Some 26,000 civilians are killed or injured every year, about half women and children. Add this to the estimated 1 million people who have been hurt or killed by land mines since 1975, and it's clear that these weapons are both a current and future threat. Land mines continue wars' terrors even after peace accords have been signed, catching people working in fields, collecting firewood, playing, or just walking down a road. They continue to maim and kill and turn typical livelihoods such as farming into high-risk endeavours. They also sabotage rehabilitation efforts. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, which is still recovering after war ended in late 1995, land mines continue to explode every month, killing or maiming some 30 people. A joint study by the ICRC and the U.N. estimates that these accidents will only increase as refugees return home through the most-heavily mined areas. Currently the worst-affected countries are Cambodia, where one in every 236 people is a land mine victim, Afghanistan and Angola; together these three account for 85 percent of the world's land mine deaths. In Angola, a country ravaged by decades of civil war, land mines have claimed an estimated 80,000 casualties. Now it bears the unenviable distinction of having one of the largest amputee populations in the world, 70,000 people—many of them children. And it may get worse. There are as many as 12 million unexploded land mines still lurking in the soil. The toll on children is heavy. Land mine injuries require many painful and expensive operations. Young victims have to replace outgrown prostheses repeatedly. A 10-year-old with a life expectancy of 60 may need 25 prostheses over time, costing thousands of dollars. These children face the difficult social ramifications of being disabled, which carries even greater disadvantage in the developing world in terms of limiting job opportunities. In countries where women have far fewer opportunities than men, girls disabled by landmines will have limited marriage possibilities. Despite an international outcry against land mines, many countries continue to produce them and they still are widely used. The most strident effort to date is 1997's Ottawa Treaty, which urges signatories to ban the use, production, stockpiling and transfer of anti-personnel mines and participate in clearing mines and assisting victims. Currently 129 countries have endorsed the treaty, including many of the leading land mine manufacturing states. The United States, China, Cuba, Iran, Iraq, Serbia, Singapore and Vietnam have not signed. Nongovernmental organizations conduct land mine awareness and clearance programs as well as rehabilitation for victims and advocacy campaigns. This work and the effectiveness of the Ottawa Treaty may turn the tide against the greed of manufacturers and cold-blooded strategies of military forces, which land mines brought together. Children's welfare has long been a matter of international concern. Both the League of Nations in 1924 and the United Nations in 1959 endorsed standards for children's rights. Children also were included under general guidelines for protecting human rights, especially during war . Although powerful statements of intergovernmental unity, none of these declarations were legally binding, and plans for implementation were vague at best. In 1979, the International Year of the Child, nations began discussions about a comprehensive document for children's rights. After 10 years of negotiations, the United Nations adopted the landmark Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989. Recognizing that the "inherent dignity and ...equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world," the CRC’s 54 articles set global precepts for children's inherent right to life, survival, development and opinions, regardless of race, religion or gender. Going further, the document asserts that the best interests of children become a high priority for governing and legislative bodies. Within a year, the necessary 20 countries ratified the treaty, and to date, 191 of the 193 countries in the world have followed suit. The United States is not among these, despite its high regard for human rights. The CRC has its critics, with some objecting to articles that place the onus of children's protection and development on governments instead of parents. However, it serves as an effective set of human rights guidelines crossing across economic, cultural and ethnic populations. Its bottom line is clear: We—individuals, organizations, and governments—need to shield and champion all children everywhere.

Conclusion The first step toward helping the world's children who are suffering in war is learning more about their plight, which you have begun by reading this article. There is a growing volume of information on this issue, much of it accessible on the web. Visit this site again for compelling stories and reports and to learn about various organizations’ programs in war rehabilitation, medical and psycho-social assistance for war-traumatized children, land mine awareness or clearance, and advocacy for children’s rights and protection. Secondly, find out what your government is doing to support global efforts to protect children's rights. Though most countries ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, that is only the first step. Carrying out its directives in measurable ways is a long-term project. The work of banning land mines in the wake of the Ottawa Treaty has also just begun; seek out any programs or laws that have emerged from it in your country. If what you find concerns you, express yourself to governmental representatives. The U.S. government, for example, has not ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, nor has it endorsed the Ottawa Treaty, and it resists international efforts to enact an 18-year minimum on the age of people admitted into armed forces. Americans who disagree with their government's stance on protecting children—all children everywhere—should contact their member of Congress. Many non-governmental organizations work with children whose lives have been affected by armed conflict. Consider helping a child in need through one of these charities. Children In Need Reports • World Week • Help a Child Copyright © 1998-2019, Children In Need Inc. |

|||||||||||||||||

Modern warfare has changed the old rules. Once, countries waged wars with each other, preceded by formal declarations, with basic standards of behavior. Now, many wars ignite between ethnic and religious factions, often within one country. No codes of conduct apply. As a result, civilians make up more than 80 percent of casualties. Tragically, many of these are children. In the last decade an estimated 2 million children died in wars. Another 1 million have been orphaned and 4 million were disabled.

Modern warfare has changed the old rules. Once, countries waged wars with each other, preceded by formal declarations, with basic standards of behavior. Now, many wars ignite between ethnic and religious factions, often within one country. No codes of conduct apply. As a result, civilians make up more than 80 percent of casualties. Tragically, many of these are children. In the last decade an estimated 2 million children died in wars. Another 1 million have been orphaned and 4 million were disabled.